Politics

Kenyatta

Kenya gained independence in 1963 with the collapse of British colonization. Kenya was named after Jomo Kenyatta, often cited as the “Father of the Nation.” He was the first president of Kenya and founder of the Kenya African National Union (KANU). Active in politics throughout the decolonization process, Kenyatta made his way to the forefront of Kenya’s political system through his position as spokesman for Kenyan nationalism, his imprisonment by colonial authorities, his organization of the Kikuyu and other political movements, and perhaps most importantly, his strong personality. As a conservative, he wanted to balance his policies and government, and he nearly always ensured that he had the popular support before making decisions. He supported the reconciliation between Europeans and Africans, and advocated for Kenya’s free enterprise economy. He maintained public support throughout his time as president, and remained president until his death from natural causes in 1978. (Nelson 54-56 1983)

Political Parties

KANU originally consisted of the Kikuyu, Luo and Kamba ethnic groups, but it was joined by Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU), an alliance of the smaller ethnic groups from the pastoral and coastal regions that wanted to resist domination by the larger ethnic groups, a year after independence (Nelson 204 1983). In 1969 the only opposition party, Kenya Peoples Union (KPU), was banned by Kenyatta’s government on the charge of planning to overthrow the government, essentially turning Kenya into a one party system (Nelson 207 1983). Despite the one party system, it was a comparatively open polity until Daniel arap Moi came into power after the death of Kenyatta. His presidency marked a new era of Kenyan politics.

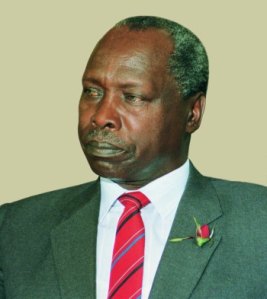

Moi

Moi’s presidency was markedly more difficult that Kenyatta’s. Two important contributing factors include the failing economy and Moi’s ethnicity and lack of popularity (Hornsby and Throup 26 1998). Kenyatta was Kikuyu, and therefore under his rule the Kikuyu dominated business, civil service, many prominent professions, and politics. Moi was a Kalenjin, and did not have the resources that Kenyatta had (Hornsby and Throup 26 1998). A coup d’état ensued in 1982, after which Moi was even less willing to trust Kikuyu advisers (Hornsby and Throup 31-32 1998). In 1983, Charles Njonjo, an attorney-General supported by Moi, competed in the vice-presidential elections and lost. His enemies warned Moi that he was going to challenge Moi’s command, and Moi made sure he fell quickly from power (Hornsby and Throup 32-33 1998). This episode increased Moi’s paranoia and once other officials saw how quickly Njonjo had fallen, only the president’s support mattered. Suddenly policies were unimportant, rival groups denounced one another continuously, and only the president’s approval was sought, beginning an authoritarian period of Kenyan politics (Hornsby and Throup 38-39 1998).

Recent Politics

Elections were held in March, 2013 which elected Jomo Kenyatta’s son, Uhuru Kenyatta, as the fourth president of Kenya. Although the elections weren’t perfect, the process went much more smoothly than the heavily flawed elections in 2007 which caused violent attacks that resulted in the death of over 1,000 people. Problems that arose were mostly technical in nature. The electronic voting system that Kenya had planned to use failed for unexplained reasons, giving Raila Odinga, the main opposition, the opportunity to claim fraud. Due to the fact that Kenyatta won with only 50.07% of the vote, the narrow margin of .07% meant there was ample room for error, according to Odinga. However, Supreme Court in Kenya ruled that the election results did not “produce any profound irregularities” (Odula 1 2013), and the election results stood. (Odula 1-2 2013).

Uhuru Kenyatta